Major Section 5.1: Implementation Proposals for the IRB Approach and Minimum Requirements for Internal Rating System (Attachment 5.4) and Risk Quantification System (Attachment 5.5)

Attachment 5.1

No: BCS 290 Date(g): 12/6/2006 | Date(h): 16/5/1427 Status: No longer applicable 5.1 Implementation Proposals for the IRB Approach and Minimum Requirements for Internal Rating System (Attachment 5.4) and Risk quantification system (Attachment 5.5)

Purpose

5.1.1 This section sets out the SAMA’s proposals for implementing the IRB Approach, including the minimum qualifying criteria for adoption of the IRB Approach in Saudi Arabia and the manner in which the SAMA intends to exercise national discretions available under the Approach.

5.1.2 The proposals are based on Basel II. SAMA will take into account the banks views and comparable criteria adopted by other supervisors before finalizing these proposals.

Implementation Approach

Availability and choice of approaches

5.1.3 SAMA plans to allow all available IRB Approaches to banks that are capable of meeting the relevant requirements. SAMA aims to make available for adoption by banks the Foundation Approach and the Advanced Approach from 1 January, 2008 and beyond. Exact timing for implementation would be subject to SAMA’s bilateral discussions with banks.

5.1.4 As a general principle, SAMA will not require or mandate any particular bank to adopt the IRB Approach. Banks should conduct their own detailed feasibility study and analysis of the associated costs and benefits in order to decide whether to use this Approach. Nevertheless, for those banks that are building the IRB systems, adopting this Approach will entail significant changes to their existing systems, the collection of extensive data as well as the fulfillment of many other quantitative and qualitative requirements. It would therefore be more practicable for such bank to start with the Foundation Approach rather than going straight to the Advanced Approach. The possibility of moving straight to the Advanced Approach is however not entirely ruled out, if banks concerned can satisfy the more stringent criteria, in particular the ability to measure Loss Given Default (LGD) and Exposures At Default (EAD).

Application / validation procedures

5.1.5 Banks wishing to adopt the IRB Approach should discuss their plans with SAMA and meet the requirements described in Attachment –5.1. Whether they will be able to use the IRB Approach for capital adequacy purposes is subject to the prior approval of SAMA and to their satisfying various qualitative and quantitative requirements relating to internal rating systems and the estimation of Probability of default (PD) Loss Given Default (LGD); Exposure At Default (EAD) and the controls surrounding them. SAMA will conduct on-site validation exercises to ensure that bank internal rating systems and the corresponding risk estimates meet the Basel requirements. It should however be stressed that the primary responsibility for validating and ensuring the quality of bank internal rating systems lies with its management.

5.1.6 In order to allow sufficient time for the SAMA to carry out the necessary validations on their systems, banks should inform SAMA no later than 30 November 2005 of their final plans in writing if they want to use the IRB Approaches. This will be followed by bilateral meetings to discuss the banks Implementation Plans and state of readiness for adopting the IRB Approaches.

5.1.7 In assessing the eligibility of a bank to adopt the IRB Approach, SAMA will adopt the examination processes as outlined in Attachment 5.I. In the case of banks that are branches of foreign banks, SAMA will liaise with the home supervisory authority particularly on the validation arrangements to assess the extent of reliance that it may place on the validation done by the home supervisor. Other aspects will include their Basel II implementation plans, National Discretion, extent of adoption of Saudi portfolios risk characteristic in their internal classification and risk estimates, etc. This approach is consistent with the Basel Concordat and should help keep duplication of supervisory attention to a minimum.

5.1.8 SAMA will provide the banks with more details regarding the application and approval/examination procedures for use of the IRB Approach. Relevant self-assessment questionnaires will also be issued to banks, to assist SAMA in evaluating banks Implementation Plans.

Proposed work programme and implementation timetable

5.1.9 SAMA will discuss with the banks through the Working Groups and bi-laterally concerning their Implementation Plans and strategies relating to the IRB Approach. These guidance rules, cover the proposals on the exercise of national discretions and the minimum qualifying criteria for transition to the IRB Approach.

5.1.10 Regarding the exercise of national discretion, SAMA has provided clear guidance in this document. Banks may seek further clarifications on national discretion items during the Working Groups meetings and on a bi-lateral basis. (Attachment - 5.3.)

5.1.11 Other rules and guidance on the IRB Approach, including the revised capital adequacy returns for users of this Approach will be issued to banks in the future.

Qualifying Criteria for Adoption of IRB Approach

5.1.12 In order for banks to be eligible to use the IRB Approach for capital adequacy purposes, they should comply with a set of minimum qualifying criteria. These requirements generally cover:

(i) The criteria for transition to the IRB Approach; and

(ii) Other requirements relating to the qualitative and quantitative aspects of IRB systems i.e. rating system (Attachment 5.4) and Risk Quantification System (Attachment 5.5).

Criteria for transition to the IRB Approach

Adoption of IRB Approach across the banking group

5.1.13 SAMA would expect banks to adopt the IRB Approach except for immaterial exposures that have been exempted by SAMA. The fundamental principle is that a clear critical mass of bank’s risk-weighted assets (“RWAs”) (as recorded in the banks solo and consolidated capital adequacy returns) would have to be on the IRB Approach before the bank could transition to that Approach for capital adequacy purposes. In this regard, the amount of immaterial exposures that can be exempt from the requirements of the IRB Approach is subject to a maximum limit of 15% of a bank’s risk-weighted assets. Exempt exposures will apply the Standardized Approach.

5.1.14A Given the data limitations associated with SL exposures, a bank may remain on the supervisory slotting criteria approach for one or more of the PF, OF, IPRE or HVCRE sub-classes, and move to the foundation or advanced approach for other sub-classes within the corporate asset class.

(Refer para 262, International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards – June 2006)

5.1.14 SAMA current proposal is that the ultimate level of IRB coverage should be at least 85% of a bank’s RWA’s, a bank may be allowed to transition before reaching this level of coverage if it can satisfy the criteria for adopting phased rollout (see paragraphs 5.1.16 to 5.1.18 below).

5.1.15 Prescribing a minimum level of IRB coverage means that some banks might not qualify to adopt IRB immediately (i.e. on 1 January 2008) but might have to wait until they have achieved the requisite level of coverage. This, SAMA believes, is preferable to a situation in which banks are approved to use IRB when in fact a very significant proportion of their RWAs are not actually on IRB. Given that use of IRB-type systems in Saudi Arabia are not well established, a certain degree of caution is considered prudent, and SAMA does not expect banks to rush to adopting IRB when they are not fully ready.

Consequently, banks planning to use the IRB Approach should conduct a well thought out and a comprehensive feasibility study.

5.1.16 Phased rollout and transition period

A bank may be allowed to adopt a phased rollout of the IRB Approach across its banking group within a transition period of up to three years subject to SAMA being satisfied with its final Implementation Plans. The implementation plan should specify, among other things, the extent and timing for rolling out the IRB Approach across significant asset classes (or sub-classes in the case of retail) and business units over time. The plan should be precise and realistic, and must be approved with SAMA. Further, when a bank adopts the IRB Approach for an asset class within a particular business unit (or in the case of retail exposures for an individual sub-class), it must apply the IRB Approach to all exposures within that asset class (or sub-class) in that unit.

5.1.17 Banks adopting phased rollout should have achieved a certain level of IRB coverage (say, at least 85% of their RWAs) before they could be allowed to use the Approach for capital calculation. By the end of the transition period, all of their non-exempt exposures should have been migrated to the IRB Approach.

5.1.18 Banks adopting the foundation or advanced approaches are required to calculate their capital requirement using these approaches, as well as the 1988 Accord for the time period specified in paragraphs 45 to 49, International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards – June 2006

(Refer para 263, International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards – June 2006)

Under these transitional arrangements banks are required to have a minimum of two years of data at the implementation of this Framework. This requirement will increase by one year for each of three years of transition.

(Refer para 265, International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards – June 2006)

Parallel run and capital floor

5.1.19 There will be a parallel run of Basel II – IRB Approach only.

5.1.20 Banks planning to use the IRB Approach will be subject to a single capital floor for the first three years after they have adopted the IRB Approach for capital adequacy purposes. They should calculate the difference between: (i) the floor as defined in paragraphs 5.1.21 and 5.1.22 below; and (ii) the amount as calculated according to paragraph 5.1.23 below. If the floor amount is larger, Banks are required to add 12.5 times the difference to RWAs. See Example-I for a simple illustration of how the floor works.

5.1.21 The capital floor is based on application of the current Accord. It is derived by applying an adjustment factor to the following amount: (i) 8% of the RWAs; (ii) plus Tier 1 and Tier 2 capital deductions; and (iii) less the amount of general provisions that may be recognized in Tier 2 capital. The adjustment factor for banks using the IRB Approach, whether Foundation or Advanced, for the First year is 95%. The adjustment factor for the Second Year is 90%, and for the Third year is 80%. Such adjustment factors will apply to banks adopting the IRB Approaches during the transition period, i.e. 3 years following the initial period. The timeframe for application of the capital floor and adjustment factors proposed here is different from that in paragraph 46 of the Basel II document. SAMA considers that these rules will ensure a level-playing field for banks that adopt the IRB Approach in different years within the transition period.

5.1.22 For banks using the IRB Approach and AMA approach for operational risk, the floor will be based on calculations using the rules of the Standardized Approach for credit risk. The adjustment factor for banks using the IRB Approaches are given below;

Application of Adjustment Factors

1st year of Implementation 2nd year of Implementation 3rd year of Implementation Basis of Comparison Foundation Approach 95% 90% 80% Current Accord Advanced IRB and or operation risk 90% 80% 70% Standardized Approach 5.1.23 In the years in which the floor applies, banks should also calculate: (i) 8% of total RWAs as calculated under Basel II; (ii) less the difference between total provisions and expected loss amount as described in Section III.G in the Basel II document; and (iii) plus other Tier 1 and Tier 2 capital deductions. Where a bank uses the Standardized Approach for credit risk for any portion of its exposures, it also needs to exclude general provisions that may be recognized in Tier 2 capital for that portion from the amount calculated according to the first sentence of this paragraph.

5.1.24 Should problems emerge during the three-year period of applying the capital floors, SAMA will take appropriate measures to address them, and, in particular, will be prepared to keep the floors in place beyond the third year if necessary.

Transition arrangements

5.1.25 The Basel Committee recommends that some minimum requirements for: (i) corporate, sovereign and bank exposures under the Foundation Approach; (ii) retail exposures; and (iii) the PD/LGD Approach to equity can be relaxed during the transition period, subject to national discretion1.

SAMA recognizes that bank wishing to adopt the IRB Approach may need an extended period of time to develop/enhance their internal rating systems to come into line with the Basel requirements and to start building up the required data for estimation of PD/LGD/EAD. Therefore, SAMA proposes to apply the transition requirement of a minimum of two years of data at the time of adopting the foundation IRB Approach.

The table below sets out SAMA’s arrangements:

Item Requirement Transition Arrangement Requirement Observation period for PD for corporate, bank, sovereign and retail exposures At least 2 years 2 years of data during the transition- same as normal requirement LGD/EAD for corporate, bank and sovereign exposures At least 7 years No transition period Reduction LGD and EADs for retail exposure At least 5 years No transition period Reduction 5.1.27 As a 2 year data observation period may not be enough to capture default data during a full credit cycle, SAMA expects banks to exercise conservatism in the assignment of borrower ratings and estimation of risk characteristics. Banks would need to demonstrate and document their methodology and work in this area.

5.1.28 SAMA will incorporate the above proposals in its final implementation document after taking into account the bank’s comments and any further discussions with the bank and after reviewing each bank’s final Implementation Plans.

Qualitative and quantitative requirements on IRB systems

General

5.1.29 The IRB Approach to the measurement of credit risk relies on banks’ internally generated inputs to the calculation of capital. To minimize variation in the way in which the IRB Approach is carried out and to ensure significant comparability across banks, SAMA considers it necessary to establish minimum qualifying criteria regarding the comprehensiveness and integrity of the internal rating systems of banks adopting the IRB Approach, including the ability for those systems to produce reasonably accurate and consistent estimates of risk i.e. PD’s LGD’s and EAD’s. SAMA will employ these criteria for assessing their eligibility to use the IRB Approach.

5.1.30 The minimum IRB requirements focus on a bank’s ability to rank order and quantify risk in a consistent, reliable and valid manner. The qualitative aspects of an internal rating system, such as rating system design and operations, corporate governance and oversight, and use of internal ratings, are detailed in the “Minimum Requirements for Internal Rating Systems under IRB Approach” Attachment-5.4. Other quantitative aspects covering risk quantification requirements and validation of internal estimates are prescribed in the “Minimum Requirements for Risk Quantification under IRB Approach” (Attachment-5.3). Apart from meeting the relevant minimum requirements, banks’ overall credit risk management practices should also be consistent with the guidelines and sound practices issued by SAMA.

5.1.31 The overarching principle behind the requirements is that an IRB compliant rating system should provide for a meaningful assessment of borrower and transaction characteristics, a meaningful differentiation of credit risk, and reasonably accurate and consistent quantitative estimates of risk. Banks using the IRB approach would need to be able to measure the key statistical drivers of credit risk. They should have in place a process that enables them to collect, store and utilize loss statistics over time in a reliable manner.

5.1.32 The proposed requirements are broadly consistent with the Basel standards. Highlighted below are some specific areas of the requirements.

Use of internal ratings

5.1.33 In order to facilitate banks to transition to IRB over time, SAMA would be flexible in applying the “use” test to a Basel II - compliant internal rating system. Banks would need to demonstrate that such a system has been used for three years prior to qualification.

If the internal rating systems of a bank which is owned by a foreign banking group, have been developed and used at the group level for some time, there may be scope for reducing the three year requirement on a case-by-case basis, depending on the level of group support (e.g. in terms of resources and training) provided to the local bank. This, however, will not absolve local management from the responsibility to understand and ensure the effective operation of the IRB systems at the bank level.

Assessment of capital adequacy using stress tests

5.1.34 For the purpose of assessment of capital adequacy using stress tests, it is proposed that stressed scenario chosen by bank should resemble an economic recession and other economic down turns experiences in KSA.

Definition of default

5.1.35 The proposed definition of default is consistent with SAMA’s regulatory definition set at 90 days. Further, there is the setting of a materiality threshold to an obligor’s credit obligations in determining whether a default is considered to have occurred with regard to the obligor after any portion of the obligor’s credit obligations has been past due for more than 90 days. The purpose of applying materiality to the definition of default is to avoid counting as defaulted obligors those that are in past due only for technical reasons. SAMA’s preliminary intention is to apply the materiality level on a conservative basis i.e. 5% or more of the obligor’s outstanding credit obligations, and banks may set a lower threshold if they choose not to apply the threshold based on their individual circumstances.

5.1.36 The second element is the application of the default definition on a “banking group” or consolidated basis. In other words, once an obligor has defaulted on any credit obligation to the banking group, all of its facilities within the group are considered to be in default. SAMA proposes that a banking group should cover all entities within the group that are subject to full consolidation.

5.1.37 The third element relates to the use of different default triggers in the definition. If a bank owned by a foreign banking group wants to use a different default trigger set by its home supervisor for particular exposures (e.g. 180 days for exposures to retail or public sector entities), the banks should be able to satisfy the SAMA that such a difference in the definition of default will not result in any material impact on the default / loss estimates generated.

Internal validation of IRB Approach

5.1.38 With regard to banks’ internal validation of the IRB Approach, SAMA considers that it should be an integral part of a banks rating system architecture to provide reasonable assurances about its rating system. Banks adopting the IRB Approach should have a robust system in place to validate the accuracy and consistency of their rating systems, processes and the estimation of all relevant risk components. They should demonstrate to SAMA that their internal validation process enables them to assess the performance of internal rating and risk estimation systems consistently and meaningfully. It is proposed that the internal validation process should include review of rating system developments, ongoing analysis, and comparison of predicted estimates to actual outcomes i.e. back-testing.

Way Forward

5.1.39 Given that implementation of the IRB Approach is a challenging task and demands significant time and resources, banks planning to use the IRB Approach on 1 January 2008 and beyond should have already completed in sufficient depth their detailed project evaluations, and their implementation plans be well advanced. They should be prepared to provide the SAMA with the full details of their implementation plan and demonstrate how they are monitoring the progress of their Implementation Plans.

5.1.40 SAMA, in the meantime, will carry on with the work of finalizing its relevant guidance (including the risk-weighting framework), the revised capital adequacy return and completion instructions as well as the approval / validation procedures for the IRB Approach for consulting with the banks during 2006.

1 There are no transition arrangements for the Advanced IRB Approach and the Market based Approach to qualify.

Appendix– 5.1

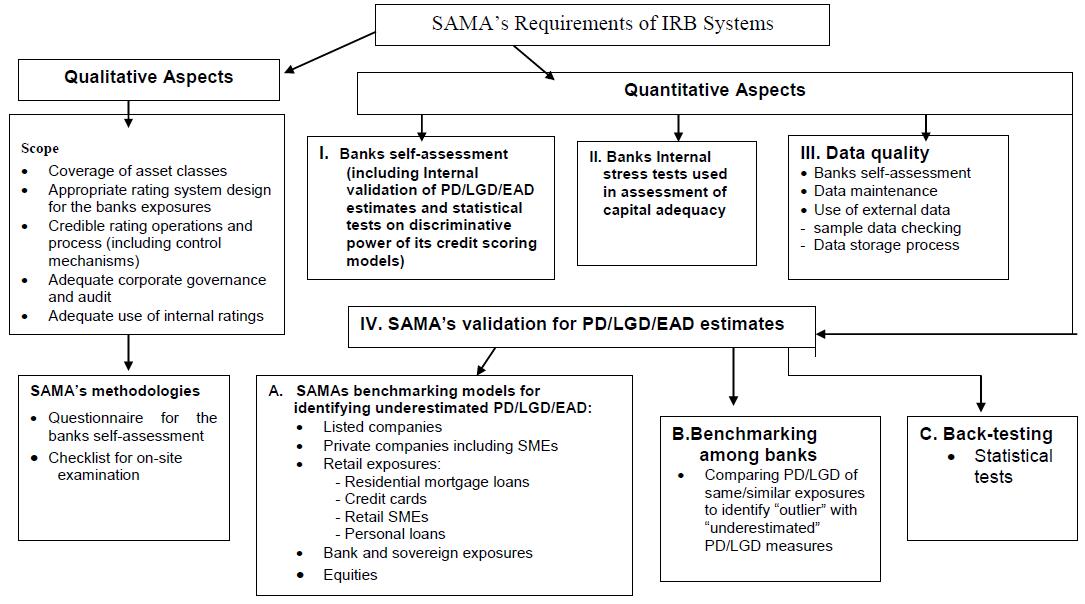

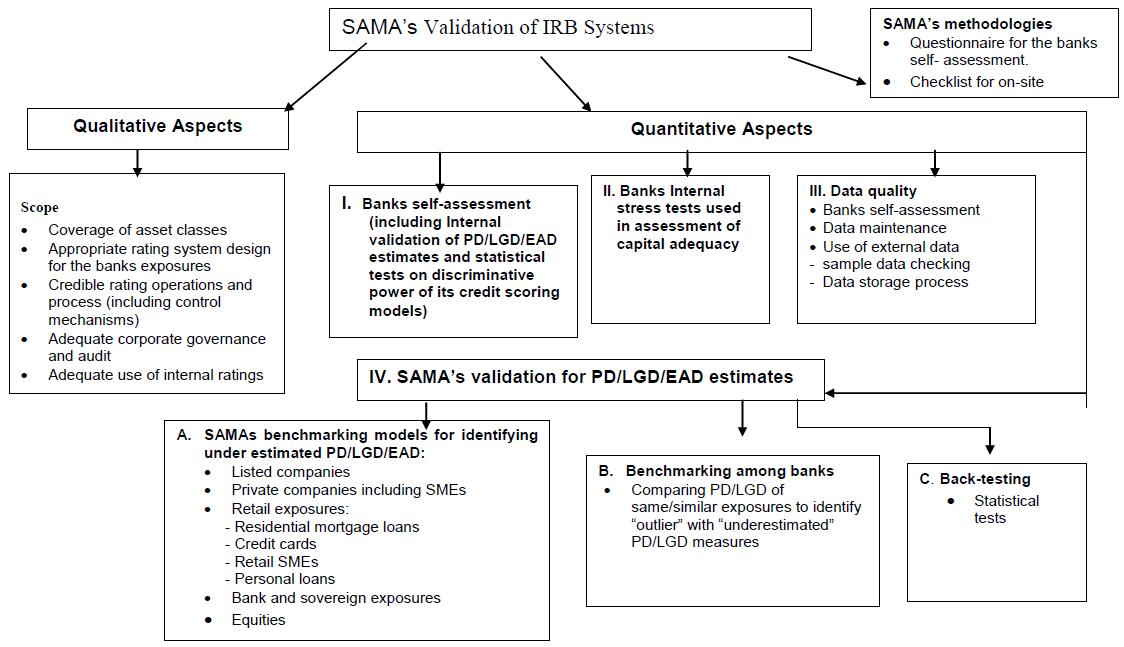

FIGURE - 1

Attachment 5.2: Calculation of Capital Floor - Numerical Example

Assumptions and calculations

Current Accord

• RWAs of a bank under the current Accord = $ 100

• Tier 1 and Tier 2 capital deductions = $ 1

• General provision recognized in Tier 2 capital = $ 0.5

(i) 8% x $ 100 + $ 1 – $ 0.5

= $ 8.5

Basel II

• RWAs of banks under Basel II

• = $ 90

• Tier 1 and Tier 2 capital deductions = $ 1

• Difference between total provisions and expected loss amount (as described in Section III.G in the Basel II Framework) = $ 0.8

(ii) 8% x $ 90 + $ 1 – $ 0.8

= $ 7.4

Calculation of Floor

• Adjustment factor of 95% is applicable

Floor = 95% x $ 8.5 in (i) = $ 8.075

As the Floor is larger than $ 7.4 in (ii), an amount equivalent to 12.5 x ($ 8.075 – $ 7.4) or $ 8.4375 should be added to the RWAs of $ 90.

Therefore, the regulatory RWAs under Basel II for calculation of the capital adequacy ratio should be $ 98.4375 (i.e. $ 90 + $ 8.4375).

Attachment 5.3: National Discretion – IRB Approach

Reference to Basel II Document Areas of National Discretion SAMA's Position 227 Definition of HVCRE. N/A 231 Establish exposure threshold to distinguish between retail and corporate. Yes 231 For residential mortgages, set limits on the maximum number of housing units per exposure. N/A 232 Set a minimum number of exposures within a pool for exposures in that pool to be treated as retail. No 237 (FN59) Debts with economic substance of equity may not be included where directly hedged by an equity holding. Yes 238 Re-characterize debt holding as equities for regulatory purposes. Yes 242 Purchased receivables: Size and concentration limits above which using the "bottom-up" approach. No 249 - 251 & 283 HVCRE: banks will be able to use the foundation or advanced approaches, similar to the corporate approach, but with a separate RW function. N/A 267 - 269 For a maximum of ten years, exempt equity exposures from the IRB treatment. No 274 Firm-size adjustment and threshold for SME based on total assets instead of total sales. Yes 277 Lower SL RWs, 75% to strong exposures and 100% to good exposures. Yes 282 HCVRE: assign preferential RW of 75% to "strong" exposures, and 100% to "good" Exposures. N/A 288 Employ a wider definition of subordinated loan for a 75% LGD under FIRB. Yes 318 - 319 Determine whether to use an explicit or implicit M adjustment under FIRB. Implicit 319 Exemption on explicit M to smaller domestic firms, those with consolidated sales and assets of less than SR. 500 million. No 321 - 322 Determine within the explicit M adjustment which instrument will apply for the carve-out from the one-year maturity floor. Yes 341 -342 Equity: which approach or approaches (market based or PD/LGD approach) will be used. Market 344 - 349 Equity: which market-based approaches [simple risk weight (SRW) or internal models method] to use. Both 356 Exclude equity whose debt obligations qualify for a zero RW under SA. No 357 Exemption for equity under legislative Programmes. No 358 Exemption for equity based on materiality Threshold. Yes 378 Assign preferential RWs to HVCRE. N/A 385 Treatment where calculated EL amount is lower than provisions. Yes 404 Require a greater number of borrowers grades than seven for non-defaulted borrowers and one defaulted. Yes 257 Phase roll out of the IRB approach across the banking group. Yes 259 Exemption from IRB for some exposures in non-significant business units that are immaterial Yes 260 Equity on IRB, even if banks opts for SA. No 264 - 265 Relaxation of data requirement for a transitional period Yes 443 Require an external audit of the bank's rating assignment process and estimation of loss characteristics Yes 452 (FN 82) For retail and PSE, default is considered if past due more than 180 days. For corporate, only for a transitional period of five years No 458 Establish more specific requirements on re-ageing No 467 Mandatory to adjust PD estimates upward for anticipated seasoning effects Yes 521 Determine other physical collateral as risk mitigant under the foundation approach that meet the criteria. Yes Attachment 5.4: Minimum Requirements for Internal Rating Systems Under IRB Approach

1. Introduction

1.1 Terminology

1.1.1 Abbreviations and other terms used in this paper have the following meanings:

• “PD” means the probability of default of a counterparty over one year.

• “LGD” means the loss incurred on a facility upon default of a counterparty relative to the amount outstanding at default.

• “EAD” means the expected gross exposure of a facility upon default of a counterparty.

• “Dilution risk” means the possibility that the amount of a receivable is reduced through cash or non-cash credits to the receivables obligor.

• “EL” means the expected loss on a facility arising from the potential default of a counterparty or the dilution risk relative to EAD over one year “IRB Approach” means Internal Ratings-based Approach.

• “SL” means Specialized lending.

• “Foundation IRB Approach” means that, in applying the IRB framework, banks provide their own estimates of PD and use supervisory estimates of LGD and EAD, and, unless otherwise specified by the SAMA, are not required to take into account the effective maturity of credit facilities.

• “Advanced IRB Approach,” means that, in applying the IRB framework, banks use their own estimates of PD, LGD and EAD, and are required to take into account the effective maturity of credit facilities. A “borrower grade” means a category of creditworthiness to which borrowers are assigned based on a specified and distinct set of rating criteria, from which estimates of PD are derived. The grade definition includes both a description of the degree of default risk typical for borrowers assigned the grade and the criteria used to distinguish that level of credit risk.

• A “facility grade” means a category of loss severity in the event of default (as measured by LGD or EL) to which transactions are assigned on the basis of a specified and distinct set of rating criteria. The grade definition involves assessing the amount of collateral, and reviewing the term and structure of the transaction (such as the lending purpose, repayment structure and seniority of claims).

• A “rating system” means all of the methods, processes, controls, and data collection and IT systems that support the assessment of credit risk, the assignment of internal risk ratings, and the quantification of default and loss estimates. Key aspects of a rating system are summarized in Table 1.

• “Seasoning” means an expected change of risk parameters over the life of a credit exposure.

1.2 Application

1.2.1 The requirements set out in this paper are applicable to locally incorporated banks, which use or intend to use the IRB Approach to measure capital charges for credit risk.

1.2.2 In the case of branches of foreign banks, all or part of their IRB systems may be centrally developed and monitored on a group basis. In applying the requirements of this paper, the SAMA will consider the extent to which reliance can be placed on the work done at the group level. Where necessary, SAMA will co-ordinate with the home supervisors of those banks regarding the assessment of the comprehensiveness and integrity of the group-wide internal rating systems adopted by their branches in Saudi Arabia. SAMA will also assess whether the relevant systems or models can adequately reflect the specific risk characteristics of the banks’ domestic portfolios.

1.3 Background and Scope

1.3.1 The IRB Approach to the measurement of credit risk for capital adequacy purposes relies on banks’ internally generated inputs to the calculation of capital. To minimize variation in the way in which the IRB Approach is carried out and to ensure significant comparability across banks, the SAMA considers it necessary to establish minimum qualifying criteria regarding the comprehensiveness and integrity of the internal rating systems of banks adopting the IRB Approach. The SAMA will employ these criteria for assessing their eligibility to use the IRB Approach.

1.3.2 This Document:

Prescribes the minimum requirements that a banks internal rating system should comply with at the outset and on an ongoing basis if it were to use the IRB Approach to measure credit risk for capital adequacy purposes; and

Sets out SAMA’s supervisory approach where a bank is not in full compliance with the minimum requirements.

1.3.3 The minimum requirements set out herein apply to both the Foundation IRB Approach, and the Advanced IRB Approach and to all asset classes1, unless stated otherwise. The standards related to the process of assigning exposures to borrower or facility grades and the related oversight, validation, etc. apply equally to the process of assigning retail exposures to pools of homogenous exposures, unless noted otherwise.

1.3.4 The minimum requirements for internal rating systems of equity exposures under the PD/LGD Approach are the same as those of the Foundation IRB Approach for corporate exposures, subject to the specifications set out in the “Risk-weighting Framework for IRB Approach”. Where banks adopt the internal models approach to calculate capital charges for equity exposures, the relevant requirements are set out in the “Minimum Requirements for Risk Quantification under IRB Approach”.

1.3.5 The quantification of default and loss estimates described in this paper should be read in conjunction with the “Minimum Requirements for Risk Quantification under IRB Approach”.

1 Under the IRB Approach, assets are broadly categorized into five classes: (i) corporate (with specialized lending as a subclass); (ii) sovereign; (iii) bank; (iv) retail; and (v) equity.

2. Composition of Minimum Requirements

2.1 Overview

2.1.1 The IRB requirements focus on a bank’s ability to rank order and quantify risk in a consistent, reliable and valid manner, and generally fall within the following categories:

(i) Rating system design;

(ii) Rating system operations;

(iii) Corporate governance and oversight;

(iv) Use of internal ratings;

(v) Risk quantification;

(vi) Validation of internal estimates;

(vii) Supervisory LGD and EAD estimates;

(viii) Requirements for recognition of leasing;

(ix) Calculation of capital charges for equity exposures – internal models approach; and

(x) Disclosure requirements.

2.1.2 The minimum requirements under categories (i) to (iv) and (x) are detailed in sections 4 to 8 below while those requirements under categories (v) to (ix) are prescribed in the “Minimum Requirements for Risk Quantification under IRB Approach”.

The overarching principle behind the requirements is that an IRB-compliant rating system should provide for a meaningful assessment of borrower and transaction characteristics, a meaningful differentiation of credit risk, and reasonably accurate and consistent quantitative estimates of risk. Banks using the IRB Approach would need to be able to measure the key statistical drivers of credit risk i.e. PD’s, LGD’s and EAD’s. They should have in place a process that enables them to collect, store and utilize loss statistics over time in a reliable manner.

2.1.4 The internal ratings and risk estimates generated by the rating system should form an integral part of the bank’s daily credit risk measurement and management process.

Generally, all banks adopting the IRB Approach should produce their own estimates of PDs and should adhere to the overall requirements for rating system design, operations, controls, corporate governance, use of internal ratings, recognition of leasing, calculation of capital charges for equity exposures, as well as the requirements for estimation and validation of PD measures. Banks wishing to use their own estimates of LGD and EAD should also meet the additional minimum requirements for these risk factors. See the “Minimum Requirements for Risk Quantification under IRB Approach” for the requirements relating to PD, LGD and EAD estimation.

3. Compliance with Minimum Requirements

3.1 Ongoing Compliance

3.1.1 To be eligible for the IRB Approach, a bank should demonstrate to the SAMA that it meets the minimum requirements at the outset and on an ongoing basis. Bank’s overall credit risk management practices should also be consistent with the guidelines and sound practices issued by the SAMA.

3.2 Supervisory Approach to Non-Compliance

3.2.1 Where a bank adopting the IRB Approach is not in full compliance with the minimum requirements, the bank should produce a plan for a timely return to compliance and seek approval from SAMA. Alternatively, the bank should demonstrate to SAMA that the effect of such non-compliance is immaterial in terms of the risk posed to the bank.

3.2.2 Failure to demonstrate immateriality or to produce and satisfactorily implement an acceptable plan will lead SAMA to reconsider the bank’s eligibility for the IRB Approach. During the period of non-compliance, SAMA will consider the need for the bank to hold additional capital under the supervisory review process, or to take other appropriate supervisory action (such as reducing its credit exposures), depending on the circumstances of each case.

4. Rating System Design

4.1 Rating Dimensions

Corporate, sovereign and bank exposures

4.1.1 Banks adopting the IRB Approach should have a two dimensional rating system that provides separate assessment of borrower and transaction characteristics. This approach assures that the assignment of borrower ratings is not influenced by consideration of transaction specific factors.

Borrower rating

4.1.2 The first dimension should reflect exclusively the risk of borrower default. Collateral and other facility characteristics should not influence the borrower rating.1 Banks should assess and estimate the default risk of a borrower based on the quantitative and qualitative information regarding the borrower’s creditworthiness (see subsection 4.4 below for risk assessment criteria). Banks should rank and group borrowers into individual grades each associated with an average PD.

4.1.3 Separate exposures to the same borrower should be assigned to the same borrower grade, irrespective of any differences in the nature of each specific transaction. Once a borrower has defaulted on any credit obligation <5% threshold> to a bank (or the banking group2 of which it is a part), all of its facilities with that bank (or the banking group of which it is a part) are considered to be in default (see the definition of default in subsection 4.2 of the “Minimum Requirements for Risk Quantification under IRB Approach”).

4.1.4 There are two exceptions that may result in multiple grades for the same borrower. First, to reflect country transfer risk3, a bank may assign different borrower grades depending on whether the facility is denominated in local or foreign currency. Second, the treatment of associated guarantees to a facility may be reflected in an adjusted borrower grade.

4.1.5 In assigning a borrower to a borrower grade, banks should assess the risk of borrower default over a period of at least one year. However, this does not mean that banks should limit their consideration to outcomes for that borrower that are most likely to occur over the next 12 months. Borrower ratings should take into account all possible adverse events that might increase a borrower’s likelihood of default (see subsection 4.5 below).

Facility rating

4.1.6 The second dimension should reflect transaction specific factors (such as collateral, seniority, product type, etc.) that affect the loss severity in the case of borrower default.

4.1.7 For banks adopting the Foundation IRB Approach, this requirement can be fulfilled by the existence of a facility dimension which may take the form of: A facility rating system that provides a measure of EL by incorporating both borrower strength (PD) and loss severity (LGD); or an explicit quantifiable LGD rating dimension,

Representing the conditional severity of loss, should default occur, from the credit facilities.

In calculating the regulatory capital requirements, these banks should use the supervisory estimates of LGD.

4.1.8 For banks using the Advanced IRB Approach, facility ratings should reflect exclusively LGD. These ratings should cover all factors that can influence LGD including, but not limited to, the type of collateral, product, industry, and purpose. Borrower characteristics may be included as LGD rating criteria only to the extent they are predictive of LGD. Banks may alter the factors that influence facility grades across segments of the portfolio as long as they can satisfy the SAMA that it improves the relevance and precision of their estimates.

4.1.9 Banks using the supervisory slotting criteria for the specialized lending (“SL”) exposures need not apply this two-dimensional requirement to these exposures. Given the interdependence between borrower and transaction characteristics in SL, Banks may instead adopt a single rating dimension that reflects EL by incorporating both borrower strength (PD) and loss severity (LGD) considerations.

Retail exposures

4.1.10 Rating systems for retail exposures should reflect both borrower and transaction risks, and capture all relevant borrower and transaction characteristics. Banks should assign each retail exposure to a particular pool. For each pool, banks should estimate PD, LGD and EAD. Multiple pools may share identical PD, LGD and EAD estimates.

4.1.11 Banks should demonstrate that this grouping process provides for a meaningful differentiation of risk and results in sufficiently homogeneous pools that allow for accurate and consistent estimation of loss characteristics at the pool level.

4.1.12 Banks should have specific criteria for slotting an exposure into a pool. These should cover all factors relevant to the risk analysis. At a minimum, banks should consider the following risk drivers when assigning exposures to a pool:

Borrower risk characteristics (e.g. borrower type, demographics such as age/occupation);

Transaction risk characteristics including product and/or collateral type. One example of split by product type is to group exposures into credit cards, installment loans, revolving credits, residential mortgages, and small business facilities. When grouping exposures by collateral type, consideration should be given to factors such as loan-to-value ratios, seasoning4, guarantees and seniority (first vs. second lien). Banks should explicitly address cross-collateral provisions, where present;

Delinquency status: Banks should separately identify delinquent and non-delinquent exposures.

1 For example, in an eight-grade rating system, where default risk increases with the grade number, a borrower whose financial condition warrants the highest investment grade rating should be rated a 1 even if the bank‘s transactions are unsecured and subordinated to other creditors. Likewise, a defaulted borrower with a transaction fully secured by cash should be rated an 8 (i.e. the defaulted grade) regardless of the remote expectation of loss.

2 The banking group covers all entities within the group that are subject to the capital adequacy regime in Saudi Arabia.

3 Country transfer risk is the risk that the borrower may not be able to secure foreign currency to service its external debt obligations due to adverse changes in foreign exchange rates or when the country in which it is operating suffers economic, political or social problems.

4 Seasoning can be a significant element of portfolio risk monitoring, particularly for residential mortgages, which may have a clear time pattern of default rates.4.2 Rating Structure

Corporate, sovereign and bank exposures

4.2.1 Banks should have a meaningful distribution of exposures across grades with no excessive concentrations, on both borrower-rating and facility-rating scales (also see paragraph 4.2.4). The number of borrower and facility grades used in a rating system should be sufficient to ensure that management can meaningfully differentiate risk in the portfolio. Perceived and measured risk should increase as credit quality declines from one grade to the next.

Borrower rating

4.2.2 Rating systems should have a minimum of seven borrower grades for non-defaulted borrowers and one for defaulted borrowers1. While banks with lending activities focused on a particular market segment may satisfy this requirement with the minimum number of grades, bank’s lending to borrowers of diverse credit quality may need to have a greater number of borrower grades.

4.2.3 In defining borrower grades, “+” or “-“ modifiers to alpha or numeric grades will only qualify as distinct grades if the bank has developed complete rating descriptions and criteria for their assignment, and separately quantifies PDs for these modified grades.

4.2.4 Banks with loan portfolios concentrated on a particular market segment and a range of default risk should have enough grades within that range to avoid undue concentration of borrowers in particular grades2. Significant concentration within a single grade should be supported by convincing empirical evidence that the grade covers a reasonably narrow PD band and that the default risk posed by all borrowers in the grade falls within that band.

4.2.5 For banks using the supervisory slotting criteria for SL exposures, the rating system for such exposures should have at least four grades for non-defaulted borrowers and one for defaulted borrowers. SL exposures that qualify as corporate exposures under the Foundation IRB Approach or the Advanced IRB Approach are subject to the same requirements as those for general corporate exposures (i.e. a minimum of seven borrower grades for non-defaulted borrowers and one for defaulted borrowers).

Facility rating

4.2.6 There is no minimum number of facility grades. Banks using the Advanced IRB Approach should ensure that the number of facility grades is sufficient to avoid facilities with widely varying LGDs being grouped into a single grade. The criteria used to define facility grades should be grounded in empirical evidence.

Retail exposures

4.2.7 The level of differentiation for IRB purposes should ensure that the number of exposures in a given pool is sufficient to allow for meaningful quantification and validation of the loss characteristics at the pool level. There should be a meaningful distribution of borrowers and exposures across pools to avoid undue concentration of a bank’s retail exposures in particular pools.

1 For the purpose of reporting under SAMA’s loan classification framework, banks should also be able to identify/differentiate defaulted exposures that fall within different categories of classified assets (i.e. Substandard, Doubtful and Loss).

2 In general, a single corporate borrower grade assigned with more than 30% of the gross exposures (before on-balance sheet netting) could be a sign of excessive concentration.4.3 Multiple Rating Methodologies/Systems

4.3.1 A bank’s size and complexity of business, as well as the range of products it offers, will affect the type and number of rating systems it has to employ. Where necessary, a bank may adopt multiple rating methodologies/systems within each asset class, provided that all exposures are assigned borrower and facility ratings and that each rating system conforms to the IRB requirements at the outset and on an ongoing basis and is validated for accuracy and consistency.

4.3.2 The rationale for assigning a borrower to a particular rating system should also be documented and applied in a manner that best reflects the level of risk of the borrower. Borrowers should not be allocated across rating systems inappropriately to minimize regulatory capital requirements (i.e. cherry-picking by choice of rating system).

4.4 Rating Criteria

4.4.1 To ensure the transparency of individual ratings, banks should have clear and specific rating definitions, processes and criteria for assigning exposures to grades within a rating system. The rating definitions and criteria should be both plausible and intuitive, and have the ability to differentiate risk. In particular, the following requirements should be observed:

• The grade descriptions and criteria should be sufficiently detailed and specific to allow staff responsible for rating assignments to consistently assign the same grade to borrowers or facilities posing similar risk. This consistency should exist across lines of business, departments and geographic locations. If rating criteria and procedures differ for different types of borrowers or facilities, banks should monitor for possible inconsistency, and alter rating criteria to improve consistency when appropriate.

• Written rating definitions should be clear and detailed enough to allow independent third parties (e.g. SAMA, internal or external audit) to understand the rating assignments, replicate them and evaluate their appropriateness. The criteria should be consistent with a banks internal lending standards and its policies for handling troubled borrowers and facilities.

4.4.2 Banks should take into account all relevant and material information that are available to them when assigning ratings to borrowers and facilities1. Information should be current. The less information a bank has, the more conservative should be its rating assignments. An external rating can be the primary factor determining an internal rating assignment. However, the bank should ensure that other relevant information is also taken into account. Banks should refer to Annex A for the relevant factors in assigning borrower and facility ratings.

SL exposures within the corporate asset class

4.4.3 Banks using the supervisory slotting criteria for SL exposures should assign these exposures to internal rating grades based on their own criteria, systems and processes, subject to compliance with the IRB requirements. The internal rating grades of these exposures should then be mapped into five supervisory rating categories. The general assessment factors and characteristics exhibited by exposures falling under each of the supervisory categories are provided Attachment.

Banks should demonstrate that their mapping process has resulted in an alignment of grades consistent with the preponderance of the characteristics in the respective supervisory category. Banks should ensure that any overrides of their internal criteria do not render the mapping process ineffective.

1 It could be difficult to address the qualitative considerations in a structured and consistent manner when assigning ratings to borrowers and facilities. In this regard, banks may choose to cite significant and specific points of comparison by describing how such qualitative considerations can affect the rating. For example, factors for consideration may include whether a borrower‘s financial statements have been audited or are merely compiled from its accounts or whether collateral has been independently valued. Formalizing the process would also be helpful in promoting consistency in determining risk grades. For example, a "risk rating analysis form" can provide a clear structure for identifying and addressing the relevant qualitative and quantitative factors for determining a risk rating, and document how grades are set.

4.5 Rating Assessment Horizon

4.5.1 Although the time horizon used in PD estimation is one year, banks are expected to apply a longer time horizon in assigning ratings. A borrower rating should represent the bank’s assessment of the borrower’s ability and willingness to contractually perform despite adverse economic conditions or the occurrence of unexpected events. In other words, the Bank’s assessment should not be confined to risk factors that may occur in the next 12 months.

4.5.2 Banks may satisfy this requirement by:

basing rating assignments on specific, appropriate stress scenarios (see subsection 5.5 below); or taking appropriate consideration of borrower characteristics that are reflective of the borrower’s vulnerability to adverse economic conditions or unexpected events, without explicitly specifying a stress scenario. The range of economic conditions should be consistent with current conditions and those likely to occur over a business cycle within the respective industry/geographic region.

4.5.3 Given the difficulties in forecasting future events and the influence they will have on a particular borrower’s financial condition, banks should take a conservative view of projected information. Where limited data are available, banks should adopt a conservative bias to their analysis.

4.5.4 Banks should articulate clearly their rating approaches (see Annex B for details of rating approaches) in their credit policies, particularly how quickly ratings are expected to migrate in response to economic cycles and the implications of the rating approaches for their capital planning process. If a bank chooses a rating approach under which the impact of economic cycles would affect rating migrations, its capital management policy should be designed to avoid capital shortfalls in times of economic stress.

4.6 Use of Models

Risk assessment techniques

4.6.1 There are generally two basic methods by which ratings are assigned: (i) a model-based process; and (ii) an expert judgement-based process. The former is a mechanical process, relying primarily on quantitative techniques such as credit scoring/default probability models or specified objective financial analysis. The latter relies primarily on personal experience and subjective judgment of credit officers1.

4.6.2 For IRB purposes, credit scoring models and other mechanical procedures are permissible as the primary or partial basis of rating assignments, and may play a role in the estimation of loss characteristics.

Nevertheless, sufficient human judgment and oversight is necessary to ensure that all relevant and material information is taken into consideration and that the model is used appropriately.

Requirements for using models

4.6.3 Banks should meet the following requirements for use of statistical models and other mechanical methods in rating assignments or in the estimation of PD, LGD or EAD:

• Banks should demonstrate that a model or procedure has good predictive power and its use will not result in distortion in regulatory capital requirements. The model should not have material biases. Its input variables should form a reasonable set of predictors and have explanatory capability.

• Banks should have in place a process for vetting data inputs into a statistical default or loss prediction model. This should include an assessment of data accuracy, completeness and appropriateness.

• The data used to build the model should be representative of the population of the bank’s actual borrowers or facilities.

• When model results are combined with human judgment, the judgment should take into account all relevant information not considered by the model. Banks should have written guidance describing how human judgment and model results are to be combined.

• Banks should have procedures for human review of model-based rating assignments. Such procedures should focus on finding and limiting errors associated with model weaknesses. Banks should have a regular cycle of model validation that includes monitoring of model performance and stability, review of model relationships, and testing of model outputs against outcomes (see section 5 of the ”Minimum Requirements for Risk Quantification under IRB Approach”).

1 In practice, the distinction between the two is not precise. In many model-based processes, personal experience and subjective judgment play a role, at least in developing and implementing models, and in constructing their inputs. In some cases, models are used to provide a baseline rating that serves as the starting point in judgment-based processes.

4.7 Documentation of Rating System Design

4.7.1 Banks should document in writing the design of their rating systems and related operations (see section 5 below on rating system operations) as evidence of their compliance with the requirements of this paper.

4.7.2 The documentation should provide a description of the overarching design of the rating system, including:

the purpose of the rating system;

portfolio differentiation; and

the rating approach and implications for a bank capital planning process.

4.7.3 Rating criteria and definitions should be clearly documented. These include:

• The relationship between borrower grades in terms of the level of risk each grade implies, and the risk of each grade in terms of both a description of the probability of default typical for borrowers assigned the grade and the criteria used to distinguish that level of credit risk;

• The relationship between facility grades in terms of the level of risk each grade implies, and the risk of each grade in terms of both a description of the expected severity of the loss upon default and the criteria used to distinguish that level of credit risk;

• Methodologies and data used in assigning ratings;

• The rationale for choice of the rating criteria and procedures, including analyses demonstrating that those criteria and procedures should be able to provide meaningful risk differentiation;

• Definitions of default and loss, demonstrating that they are consistent with the reference definitions set out in subsections 4.2 and 4.3 of the “Minimum Requirements for Risk Quantification under IRB Approach”; and

• The definition of what constitutes a rating exception (including an override).

4.7.4 Documentation of the rating process should include the following key topics as a minimum. The Format and size is at the discretions of the banks.

• The organization of rating assignment;

• Responsibilities of parties that rate borrowers and facilities;

• Parties that have authority to approve exceptions (including overrides);

• Situations where exceptions and overrides can be approved and the procedures for such approval;

• The procedures and frequency of rating reviews to determine whether they remain fully applicable to the current portfolio and to external conditions, and parties responsible for conducting such reviews;

• The process and procedures for updating borrower and facility information;

• The history of major changes in the rating process and criteria, in particular to support identification of changes made to the rating process subsequent to the last supervisory view1; and

• The rationale for assigning borrowers to a particular rating system if multiple rating systems are used.

4.7.5 In respect of the internal control structure, the documentation should cover the following:

• The organization of the internal control structure;

• Management oversight of the rating process;

• The operational processes ensuring the independence of the rating assignment process; and the procedure, frequency and reporting of performance reviews of The rating system (on rating accuracy, rating criteria, rating processes and operations), and parties responsible for conducting such reviews.

4.7.6 Banks employing statistical models in the rating process should document their methodologies. The documentation should include:

• A detailed outline of the theory, assumptions and/or mathematical and empirical basis of the assignment of estimates to grades, individual borrowers, exposures, or pools, and the data sources used to estimate the model;

• The guidance describing how human judgment and model results are to be combined;

• The procedures for human review of model-based rating assessments;

• A rigorous statistical process for validating the model; and

• Any circumstances under which the model does not work effectively.

4.7.7 Use of a model obtained from a third-party vendor that claims proprietary technology is not a justification for exemption from documentation or any other requirements for internal rating systems. The burden is on the model’s vendor and the bank to satisfy SAMA.

1 The supervisory review could be a review conducted by either the SAMA or the home supervisor of the bank concerned (in the case of a foreign bank branch).

5. Rating System Operations

5.1 Coverage of Ratings

5.1.1 For corporate, sovereign and bank exposures, each borrower and all recognized guarantors should be assigned a rating and each exposure should be associated with a facility rating as part of the loan approval process. Similarly, for retail exposures, each exposure should be assigned to a pool as part of the loan approval process.

5.1.2 Each separate legal entity to which a bank is exposed should be separately rated. A bank should demonstrate to SAMA that it has acceptable policies regarding the treatment of individual entities in a connected group, including circumstances under which the same rating may or may not be assigned to some or all related entities.

5.2 Integrity of Rating Process

Corporate, sovereign and bank exposures

5.2.1 Banks should ensure the independence of the rating assignment process. Rating assignments and periodic rating reviews should be completed or approved by a party that does not stand to benefit from the extension of credit. Credit policies and approval/review procedures should reinforce and foster the independence of the rating process.

5.2.2 Borrowers and facilities must have their ratings refreshed at least on an annual basis. Certain credits, especially higher risk borrowers or problem exposures, must be subject to more frequent review. In addition, banks must initiate a new rating if material information on the borrower or facility comes to light.

(Refer para 425, International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards – June 2006)

5.2.3 In addition, borrower and facility ratings should be reviewed whenever material information on the borrower or facility comes to light1. Bank should establish an effective process to obtain and update relevant and material information on the borrower’s financial condition, and on facility characteristics that affect LGD and EAD (e.g. the condition and value of collateral).

Retail exposures

5.2.4 Banks should review the loss characteristics and delinquency status of each identified risk pool at least on an annual basis. It should include a review of the status of individual borrowers within each pool as a means of ensuring that exposures continue to be assigned to the correct pool. This requirement may be satisfied by review of a representative sample of exposures in the pool.

1 The rating should generally be updated within 90 days for performing borrowers and within 30 days for borrowers with weakening or deteriorating financial condition.

5.3 Overrides

5.3.1 Banks should clearly articulate the situations where human judgment may override the inputs or outputs of the rating process. They should identify overrides and separately track their performance.

5.3.2 For model-based ratings, banks should have guidelines and processes for monitoring cases where human judgment has overridden the model’s rating, variables were excluded or inputs altered. These guidelines should include identifying personnel that are responsible for approving the overrides.

5.3.3 For ratings based on expert judgment, banks should clearly articulate the situations where staff may override the outputs of the rating process, including how and to what extent such overrides can be used and by whom.

5.4 Data Maintenance

5.4.1 Banks should collect and store data on key borrowers and facility characteristics to support their internal credit risk measurement and management process and to enable them to meet the requirements of this paper. The data collection and IT systems should serve the following purposes:

• Improve banks’ internally developed data for

• PD/LGD/EAD estimation and validation;

• Provide an audit trail to check compliance with rating criteria;

• Enhance and track predictive power of the rating system;

• Modify risk rating definitions to more accurately address the observed drivers of credit risk; and

• Serve as a basis for supervisory reporting.

5.4.2 The data should be sufficiently detailed to allow retrospective reallocation of borrowers and facilities to grades (e.g. if it becomes necessary to have finer segregation of portfolios in future).

5.4.3 Furthermore, banks should collect and retain data relating to their internal ratings as required under [the disclosure rules].

Corporate, sovereign and bank exposures

5.4.4 Bank should maintain complete rating histories on borrowers and recognized guarantors, which include:

• The ratings since the borrower/guarantor was assigned a grade;

• The dates the ratings were assigned;

• The methodology and key data used to derive the ratings;

• The person/model responsible for the rating assignment;

• The identity of borrowers and facilities that have defaulted, and the date and circumstances of such defaults; and

• data on the PDs and realized default rates associated with rating grades and rating migration.

5.4.5 Banks adopting the Advanced IRB Approach should also collect and store a complete history of data on facility ratings and LGD and EAD estimates associated with each facility. These include:

• The dates the ratings were assigned and the Estimates done;

• The key data and methodology used to derive the facility ratings and estimates;

• The person/model responsible for the rating

• assignment and estimates;

• Data on the estimated and realized LGDs and

• EADs associated with each defaulted facility;

• Data on the LGD of the facility before and after evaluation of the credit risk mitigating effects of the guarantee/credit derivative; and

• Information on the components of loss or recovery for each defaulted exposure, such as amounts recovered, source of recovery (e.g. collateral, liquidation proceeds and guarantees), time period required for recovery, and administrative costs.

5.4.6 Banks utilizing supervisory estimates under the Foundation IRB Approach are encouraged to retain:

• Data on loss and recovery experience for corporate exposures under the Foundation Approach; and

• Data on realized losses for SL exposures where supervisory slotting criteria are applied.

Retail exposures

5.4.7 Banks should collect and store the following data:

• Data used in the process of allocating exposures to pools, including data on borrower and transaction risk characteristics used either directly or through use of a model, as well as data on delinquency;

• Data on the estimated PDs, LGDs and EADs associated with pools of exposures;

• The identity of borrowers and details of exposures that have defaulted; and

• Data on the pools to which defaulted exposures were assigned over the year prior to default and the realized outcomes on LGD and EAD.

5.5 Stress Tests Under IRB Approaches

5.5.1 Banks adopting the IRB Approaches should implement sound stress-testing processes for use in their assessment of capital adequacy. Stress testing should identify possible events or changes in economic conditions that could have unfavorable effects on a banks’ credit exposures, and assess the bank’s ability to withstand such changes. Stress tests conducted by a bank should cover a wide range of external conditions and scenarios, and the sophistication of techniques and stress tests used should be commensurate with the bank’s activities.

5.5.2 Described below are some common risk factors that are relevant to and need to be considered in credit risk stress tests:

• Counterparty risk characterized by the increase in PDs (e.g. the rise in delinquencies and charge offs) and worsening of credit spreads. Banks should be aware of the major drivers of repayment ability, such as economic/industry downturns and significant market shocks, that will affect entire classes of counterparties or credits;

• Concentration risk in terms of the exposures to individual counterparties, industries, market sectors, countries or regions. Banks should assess the contagion effects and possible linkages between different markets, countries and regions as well as the potential vulnerabilities of emerging markets;

• Market or price risk arising from adverse changes in asset prices (e.g. equities, bonds and real estate) and their impact on relevant portfolios, markets and collateral values; and

• Liquidity risk as a result of the tightening of credit lines and market liquidity under stressed situations.

5.5.3 Banks should determine the appropriate assumptions for stress-testing risk factors included in a particular stress scenario, and formulate the stressed conditions based on their own circumstances. In designing stress scenarios, banks should review lessons from history and tailor the events, or develop hypothetical scenarios, to reflect the risks arising from latest market developments.

5.5.4 SAMA will consider the results of stress tests conducted by a bank and how these results relate to its capital plans.

5.5.5 In addition to the general stress tests described above, banks should conduct a regular credit risk stress tests to assess the effect of certain specific conditions on their total regulatory capital requirements for credit risk. The tests should be meaningful and reasonably conservative. For this purpose, banks should at least consider the effect of mild recession scenarios on their PDs, LGDs and EADs. Where a bank operates in several markets, it need not conduct such a stress test in all of those markets, but it should stress portfolios containing the majority of its total exposures.

5.5.6 At a minimum, a mildly stressed scenario chosen by a bank should resemble the economic recession in Saudi Arabia in the past. Banks should assess the impact of this stress scenario based on a one-year time horizon and take into account the lag effect of an economic downturn on their credit exposures.

5.5.7 Banks may use either a static or a dynamic test to calculate the impact of the stress scenario1.

5.5.8 Where the results of a bank’s stress test indicate a deficiency of the capital calculated based on the IRB Approach (i.e. the capital charge cannot cover the losses based on the stress-testing results), SAMA will discuss this deficiency with the bank’s management. Depending on the circumstances of each case, SAMA will require the bank to reduce its risks and/or to hold additional capital/provisions, so that existing capital resources could cover the minimum capital requirements under the IRB Approach plus the result of a recalculated stress test.

5.5.9 Through the review of stress-testing results, regulatory capital could be calculated based on a more forward-looking basis, thereby reducing the impact of rising capital requirements during an economic down turn.

1 A static test considers the impact of a stress scenario on a fixed portfolio. A dynamic test typically involves modeling the evolution of a stress scenario through time (possibly including elements such as changes in the composition of a portfolio).

6. Corporate Governance and Oversight

6.1 Corporate Governance

6.1.1 Effective oversight by a bank’s Board of Directors and senior management is critical for sound risk rating system operations.

6.1.2 The Board (or an appropriate delegated committee i.e. Audit Committee) and senior management should approve key elements of the risk rating and estimation processes. These parties should possess a general understanding of the bank’s risk rating system and detailed comprehension of its associated management reports. Information provided to the Board (or the appropriate delegated committee) should be sufficiently detailed to allow the directors or committee members to confirm the continuing appropriateness of the banks rating approach and to verify the adequacy of the controls supporting the rating system.

6.1.3 Senior management should:

• Have a good understanding of the rating system’s design and operations, and approve material differences between established procedures and actual practice;

• Ensure, on an ongoing basis, that the rating system is operating properly;

• Meet regularly with staff in the credit control function to discuss the performance of the rating process, areas requiring improvement, and the status of efforts to improve previously identified deficiencies; and

• Provide notice to the Board (or the appropriate delegated committee) of material changes or exceptions from established policies that will materially impact the operations of the bank’s rating system.

6.1.4 Information on internal ratings should be reported to the Board (or the appropriate delegated committee) and senior management regularly. The scope and frequency of reporting may vary with the significance and type of information and the rank of the recipient. The reports should cover the following information:

• Risk profile by grade;

• Risk rating migration across grades;

• Estimation of relevant parameters per grade;

• Comparison of realized default rates (LGDs and EADs where applicable) against expectation;

• Reports measuring changes in regulatory and economic capital;

• Results of credit risk stress-testing; and

• Reports generated by rating system review, audit, and other control units.

6.2 Credit Risk Control

6.2.1 Banks should have independent credit risk control units that are responsible for the design or selection, implementation and performance of their internal rating systems. The unit(s) should be functionally independent from the staff and management functions responsible for originating exposures. Areas of responsibility should include:

• Design of the rating system;

• Testing and monitoring internal grades;

• Reviewing the compliance with policies and procedures, including application of rating criteria, processes of overrides and policy exceptions;

• Producing and analyzing summary reports from the banks’ rating system, to include historical default data sorted by rating at the time of default and one year prior to default, grade migration analyses, and monitoring of trends in key rating criteria;

• Implementing procedures to verify that rating definitions are consistently applied across departments and geographic areas;

• Reviewing and documenting any changes to the rating process, including the reasons for changes;

• Reviewing the rating criteria to evaluate if they remain predictive of risk. Changes to the rating process, criteria or individual rating parameters should be documented and retained for SAMA to review; and participating in the development, selection, implementation and validation of rating models; and

• Assuming oversight and supervisory responsibilities for any models used in the rating process, and ultimate responsibility for the ongoing review of and alterations to rating models.

6.3 Internal and External Audit

6.3.1 Internal audit or an equally independent function should review at least annually a bank’s rating system and its operations, including the operations of the credit function and the estimation of PDs, LGDs and EADs. Areas of review include adherence to all applicable minimum requirements.

6.3.2 Internal audit should document its findings and report them to the Board (or the appropriate delegated committee) and senior management. The findings would facilitate the bank to disclose information in relation to its rating processes and controls surrounding these processes, which is required under Pillar-III.

6.3.3 SAMA may commission an external audit under Banking Control Law to review rating assignment process and estimation of loss characteristics or risk drivers i.e. PD, LGDs and EAD’s where necessary.

6.4 Staff Competence

6.4.1 Senior management should ensure that the staff responsible for any aspect of the rating process, including credit risk control and internal validation, are adequately qualified and trained to undertake the role. In particular, staff responsible for assigning or reviewing ratings should receive adequate training to generate consistent and accurate rating assignments.

7 Use of Internal Ratings

7.1 Use Test

7.1.1 Internal ratings and default and loss estimates should play an essential role in the credit approval, risk management, internal capital allocations, and corporate governance functions of bank using the IRB Approach.

7.1.2 Rating systems and estimates designed and implemented exclusively for the purpose of qualifying for the IRB Approach and used only to provide IRB inputs are not acceptable.

7.1.3 It is recognized that bank may not necessarily be using exactly the same estimates for both IRB and all internal purposes. For example, pricing models are likely to use PDs and LGDs relevant to the life of the asset. Where there are such differences, banks should document their justifications.

7.2 Credible Track Record

7.2.1 A bank should have a credible track record in the use of information generated by its internal rating system. The bank should demonstrate that it has been using a rating system that was broadly in line with the requirements of this document for at least three years prior to qualification. Improvements to a bank’s rating system will not render the bank non-compliant with this requirement.

7.2.2 If the internal rating systems of a bank, which is owned by a foreign bank, have been developed and used at the group level for an extended period of time, the bank is still required to meet the “use” test locally. Nevertheless, there may be scope for the SAMA to consider whether the two-year requirement can be reduced on a case-by-case basis, depending on the level of group support (e.g. in terms of resources and training) provided to the local branch.

7.2.3 Banks adopting a phased rollout of the IRB Approach should demonstrate that they have met the “use” test in respect of individual rating systems prior to their rollout. In the case of a rating system that is applicable to different exposures (or segments of a portfolio) with different rollout dates, SAMA will regard the rating system as having met the “use” test if that system has already fulfilled the three- years requirement for a material portion (say, at least 50%) of the exposures covered by the system.

8 Disclosure Requirements

8.1 In order to be eligible for the IRB Approach, banks should meet the requirements set out in the disclosure rules under Pillar III. Failure to meet the disclosure requirements will render a bank ineligible to use the relevant IRB Approach.

Table 1: Summary of Key Aspects of an Internal Rating System

(A) Requirements (B) Rating Process (C) Use of Ratings Rating structure: Rating assignment: Credit risk measurement and management: - Maintain a two-dimensional system.

- Appropriate gradation.

- No excessive concentration in a single grade

- Ratings assigned before lending/investing.

- Independent review of ratings assigned at origination.

- Comprehensive coverage of ratings.

- Credit approval

- Loan pricing

- Reporting of risk profile of portfolio to senior management and board of directors.

- Analysis of capital adequacy, reserving and profitability of Banks

Key data requirements: Rating review: Stress test used in assessment of capital adequacy: - Probability of default (PD)

- Loss given default (LGD)

- Exposure at default (EAD)

- History of borrower defaults

- Rating decisions

- Rating histories

- Rating migration.

- Information used to assign the ratings

- Party/model that assigned the ratings

- PD/LGD estimate histories

- Key borrower characteristics and facility information.

- Independent review (annual or more frequent depending on loan quality and availability of new information) by control functions such as credit risk control unit, internal and external audit.

- Oversight by senior management and board of directors.

- Stress-testing should include specific scenarios that assess the impact of rating migrations.

- Three areas that banks could usefully examine are economic or industry downturns, market risk events and liquidity conditions.

System requirements: Internal Validation: Disclosure of key internal rating information: - The IT system should be able to store and retrieve data for exposure aggregation, data collection, use and management reporting.

- A robust system for validating the accuracy and consistency of rating systems, processes, and risk estimates.

- A process for vetting data inputs.

- Compare realized default rates with estimated PDs.

- Disclosure of items of information as started under (the disclosure rules).

Annex A : Assessment Factors in Assigning Ratings

A1 Borrower Ratings